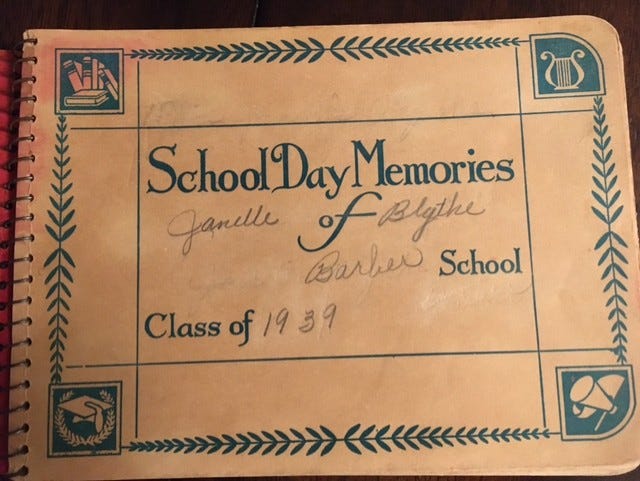

A few years before my grandmother died in 2017 we moved her into an assisted-living facility, and sometime in the process of going through the things at her house, I found this:

This was, I suppose, her version of a high school yearbook. The year was 1938, and my grandmother’s friends had signed the pages with little rhymes I thought I would share with you, because it’s hard to hold anything right now. Hard to focus. Hard to think, and breathe.

I’ve kept the cute misspellings and only changed the format to make the entries a bit easier to read. These are from a different world, a different lifetime ago. The kids signing my grandmother’s book were teenagers. They had the whole world in front of them. We’re going to pretend for a few minutes that World War Two wouldn’t soon change the world, and we’re going to pretend today in 2025 that everything is going to come out ok, because my grandmother made it, and my grandfather made it through the war, else I would not be here to write to you.

Sometimes, especially early in the morning, I like to imagine my grandmother reading this little book of poems while my grandfather was away at war. I like to imagine her tucking them away afterward and coming across them every few years while cleaning or organizing. I like to imagine her being happy that I have them now, and that I am sharing them with you.

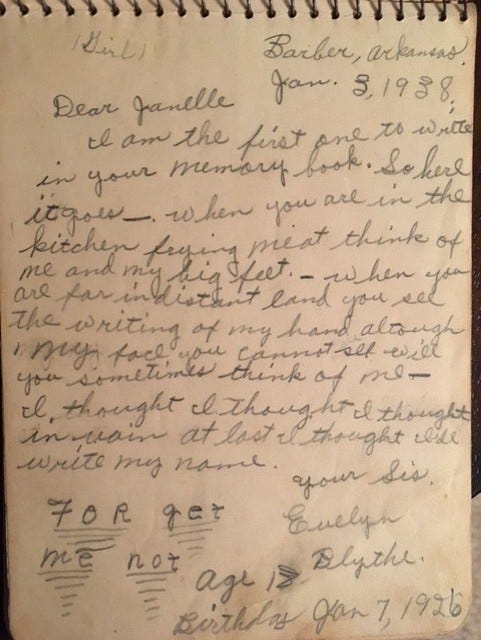

Dear Janelle,

Barber, Arkansas. Jan 3, 1938

I am the first to write in your Memory book. So here it goes—.

When you are in the kitchen frying meat,

think of me and my big feet.

When you are far in distant land,

You see the writing of my hand.

Although my face you cannot see,

Will you sometimes think of me?

I thought I thought I thought in vain,

At last I thought I’d write my name.

Your Sis,

Evelyn Blythe

Age 13. Birthday Jan. 7, 1926

(This first one was written by her actual sister, Evelyn. Evelyn lived in Texas when I knew her. She was the Texas version of my grandmother. She once told a teenage boy she would stomp him into a greasy spot on the sidewalk because he pushed my 10 year-old brother. She would have, too. Don’t mess with Texas. I digress.)

Dearest Janelle,

I am glad to rite in your memorie book.

When I am dead and allmost roten,

Grab you a spoon and come a trotting.

When you are married and live on a hill,

Send me a kiss by the whip—will.

Your Best friend,

Wayne Halland

Dearest Janelle,

You are one of my best. I wish you much success in life.

When you are married and live across the sea,

Huck up your donkey and come to see me.

Your friend,

Velta Cochran.

Virgil Thomas didn’t even bother with an introduction and just went straight for the poetry:

When you get married and have a lot of trouble,

Spank your kids with a red-hot shovel.

When you are old and cannot see,

Put on your specks and think of me.

Maida Day Harwell wins the award for most poetic. She wrote:

When twilight brings the curtains down,

And pins it with a star,

Remember, Janelle, you have a friend,

No matter where you are.

Carl Ford wins for the worst poem:

An old white hen with eight little chickens,

And love to beat the dickens.

Carl’s rhythm and meter are off, but I’m not demeaning Carl, because there’s something cool about rhyming chickens and dickens—I just wish he had rhymed it with Charles Dickens.

A note written in my grandmother’s hand on one of the pages says that AG Holland died May 22, 1939, only a few months after he signed my grandmother’s book. He was 16.

Some people left cryptic notes I wish I could decipher, like “I always laugh when I think of the day we went to the Barber bridge,” causing me to wonder what my grandmother did at the bridge to make Martha Green laugh. And how long did Martha Green remember what my grandmother did? And did she still laugh? Did my grandmother give her joy across the great span of her life?

Marie Waggoner took a trad wife angle:

When you get married I wish you much joy,

I wish you first a baby boy.

When his hair begins to curl,

I wish you then a baby girl.

If that won’t do, I wish you two.

But my grandmother did have a baby boy, and when his hair began to curl, right about the time my grandfather was called to Korea, she had a baby girl who would later, after a couple more international conflicts, have two sons, me being one of them.

Some people didn’t include a rhyme. But a girl named Nabane or Wabane wrote “I shall always want to be a link in your chain of memories,” a sentence that does something to my insides, like I can see the line of these words to my grandmother, carried down in this little book through the years, in one drawer or another in one house or another in one state or another, finally coming to me, close to a century and several states away.

I don’t know what these poems are supposed to mean, except that people want to be remembered. That life will tear us apart. That our words reach far beyond us, through space and time. Most of the entries are in pencil. They have faded so soft my old eyes have trouble reading them. I hold them up to the light, squinting to make out the fading words. I’ve been meaning to copy them all down, to carry them all on, because I can’t stand the thought of them not being read. I hate that my grandmother is no longer here to sing the silly songs she sang to me and my brother and my cousins and my daughters. I don’t like for stories to die.

So here I am telling you the story about the little book and its little rhymes, its little ways of remembering one another in 1938, before the world went to war. And it comes to you in your home or in the coffeeshop or out walking along the street in 2025, and perhaps you smile and perhaps you recall a distant grandmother, a faint and vague memory, a funny limerick from long ago. Maybe it feels like we are at war now, and this helps you forget the atrocities we visit upon one another and instead focus on how we find one another.

How we remember one another. How we keep each other alive. How we shout that we were here, once, long ago, before the world moved on without us.

Oh, these are wonderful. The quaint language, the youthful humor. How great that you're preserving your family artifacts. When my mother died, my brother and I had to sort through a lifetime of such artifacts, including diaries and letters written by my grandmother, who escaped tsarist Russia at age 18 around 1916. Some were in Russian, Yiddish. We don't know what to do with it all. Who will care? Who will want to decipher their handwriting?

Omg this is so beautiful. 😭❤️ I used to pore over my mother's high school yearbooks as a child, just fascinated by the fact that my mom had this whole entire life before me. I would read all the notes written by her friends and I would do the same thing that you do, I would let my mind wander and wonder about the exact scenarios that might have led to a cryptic piece of scribble in that yearbook. It was precious to me and I wish I had it today.